My goodness, is Starship Troopers an under-appreciated movie. It’s also a strange movie, even by ’90s standards. It shares a space with Demolition Man, representing satirical sci-fi movies that, now, have more or less become a punchline. Demolition Man—while it’s admirable for what it was trying to do—suffers from poor execution. But Starship Troopers hits the exact mark it’s going for; it’s just largely misunderstood by audiences.

The thing is, if you watch Starship Troopers with a straight face, it doesn’t work all that well. It’s weirdly melodramatic, the performances aren’t all that good, and the antagonists are just giant bugs, amongst other things. It can be seen as “one-dimensional” or “immature,” as Roger Ebert, and other critics, have complained. But, as with all Paul Verhoeven movies, Starship Troopers is not meant to be watched with a straight face. Verhoeven makes movies with his tongue buried so deep in his cheek it almost comes through the other side, and that penchant for taking something very serious not seriously at all is one of the things that makes Starship Troopers so uniquely great.

The story in Starship Troopers is pretty simple: in the near-ish future, humans have begun to colonize far-off worlds, and in our travels, we sparked a war with a species of bug-aliens. We follow Rico, played by Casper Van Dien, as he defies his parents’ wishes for him to attend Harvard by joining the military because he wants to follow his girlfriend Carmen (Denise Richards). She goes to flight school, he’s a grunt, and they soon break up—but it all works out, because just as Rico followed Carmen, Dizzy (Dina Meyer), Rico’s football (if that’s what you call the strange sport they play?) teammate, followed Rico into the military because of her feelings for him. And in the spaces between, they train under a hard-ass drill sergeant, they watch Buenos Aires get incinerated by the bugs, then they go to war.

While there’s nothing especially unique about the story itself, its effectiveness isn’t diminished by its lack of originality. Not in the least. Verhoeven directs with such bravado and the same sharp satirical eye that played no small role in vaulting Robocop (which he directed in 1987, from a screenplay by Ed Neumeier, who also penned Starship Troopers) to become, arguably, one of the best sci-fi movies ever made. Starship Troopers is a movie about war, yet Verhoeven manages, with a deft hand, to display admiration for the military at times while eviscerating it at other times (though, to be fair, the admiration exists mainly to make the evisceration all the more potent).

That is what makes this movie so effective—Verhoeven, when he’s at his best, is a master of tone. There’s little doubt that the message behind Starship Troopers is anti-military, anti-fascism, anti-war. It goes without saying that those are all salient moral and political issues that humanity has contended with for years and years. But Verhoeven doesn’t deliver them seriously, not the way other directors would. He manages to build real camaraderie between Rico, Dizzy, Ace (played to perfection by Jake Busey), and the rest of the grunts. You get to kind of like them. The grunts bond in an endearing way, and while the movie plays most of its relationships with a bit too much melodrama and silliness, they still feel honest. But that camaraderie, and the zeal for war that binds the characters together, is underscored by the horrors they endure—which Verhoeven handles with the same steady hand. When one of Rico’s men gets his head blown off in a training exercise, it’s horrifying—but also, dare I say, a little funny. You’re not supposed to laugh, but because of the shock of the moment, and the over-the-top way it happens, you laugh in self-defense. But that’s what satire, and Verhoeven, does best: you laugh when you’re supposed to be crying.

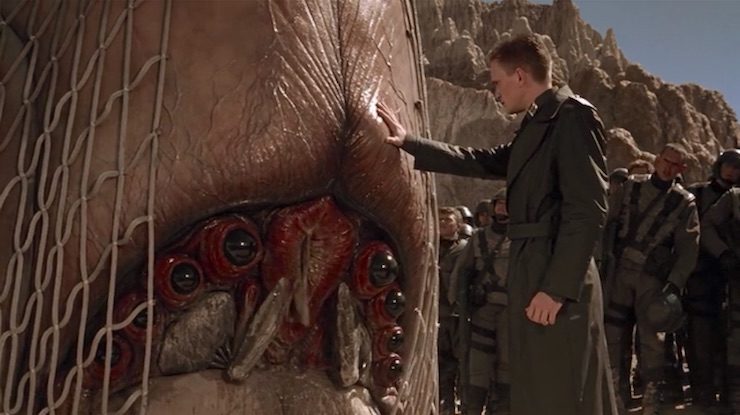

Again, if you watch Starship Troopers at a straight-ahead angle, it’s not a great movie. The drama is hokey, the performances are mostly flat, and the story doesn’t do much to engage its audiences. The trick, as with most—if not all—Verhoeven movies, is to shift your point of view by a few degrees to capture how powerful Verhoeven’s storytelling is. In typical war movies, you have a clear message: war is hell. Characters go through hellish boot camp, are shipped off to a hellish war, then they die in hellish fashion or live to face a lifetime of trauma. Everyone gets what they pay for. But in Starship Troopers, not everyone thinks war is hell. In fact, a lot of them come to think it’s pretty awesome, which, if you look around the United States alone, you find that’s not an uncommon perception. Verhoeven hits us where it counts by not just damning war itself, but also our celebration of war. It’s no coincidence that more than one character meets a gruesome end soon after congratulating themselves on doing war right. In a decisive moment, Dizzy is literally torn apart after cheering her own success annihilating a tanker bug. If that’s not a clear portrait of how Verhoeven is actively tearing apart the happy jingoism of our military-industrial complex, I’m not sure what is.

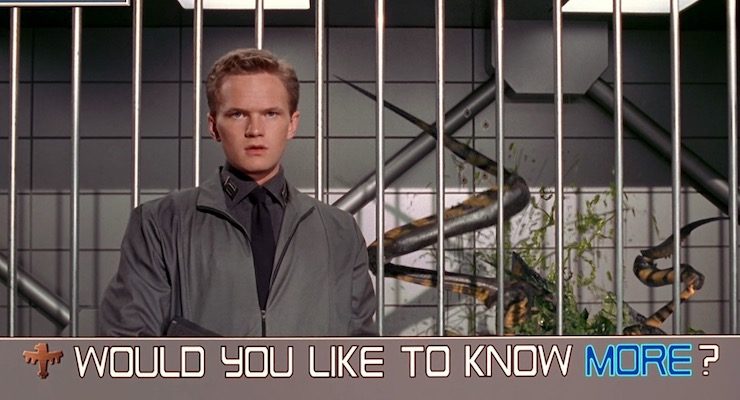

Satirizing war—condemning war—is easy. What’s not easy is extending the tragedy of war beyond the politicians, beyond the world leaders, beyond those higher-ups that are typically held responsible and laying some of that blame on our shoulders—us watching at home—as well. To great effect, Verhoeven uses news footage to give context to the world beyond the story, showing us the broader strokes of the war—the galactic politics, and so on. It’s a technique he similarly deployed in Robocop, using media not only to further develop the world, but to establish a sense of voyeurism that brings us closer to the act. As a viewer, you become complicit with the mayhem plaguing Detroit, or the war machine that grinds out pointless death after pointless death. Famously, one of the newsreels in Starship Troopers asks “would you like to know more?” Well, yes. Of course we would. We have news streaming into our brainpieces 24/7, assuring us that things are terrible somewhere, if not everywhere. This question that Starship Troopers poses is almost rhetorical because there’s at least part of us that loves the mayhem, that loves the war machine. There’s a “thin line between entertainment and war,” according to Rage Against the Machine, and Starship Troopers shows us just how thin that line can be.

There’s no shortage of ways to understand Starship Troopers. While the newsreels can be seen as a device for voyeurism, they can also be understood as a brainwashing tool, indoctrinating every able-bodied “civilian” (you’re not a “citizen” until you serve in the military) to believe violence is the answer to pretty much everything, as Rico’s high school history teacher—and eventual squad commander—Rasczak (Michael Ironside, in one of his best tough-as-nails roles) tells him. There’s the fascist bent as well, which especially smacks you in the face when you see Rico’s buddy Carl (Neil Patrick Harris, of all people) accelerate so high in the ranks that he gets to don garb that literally makes him look like a commander in the German Reich. And, for bonus points, it can also be held up to its source, the Robert A. Heinlein novel, which pretty much is the celebration of militarism and imperialism that Verhoeven is sending up.

Starship Troopers’ only sin is taking itself lightly when it was expected, apparently, to be more serious. But if you recognize that it captures the same tragic glee and manic satire that drove Robocop, Starship Troopers can easily be appreciated as something special.

“Would you like to know more?” Then give it a rewatch (provided you don’t love it already, that is); you’ll be glad you did.

Michael Moreci is a comics writer and novelist best known for his sci-fi trilogy Roche Limit. He’s also a Star Wars obsessive, who is lucky to spend his time playing Star Wars action figures with his two sons by day and writing Star Wars-inspired stories by night. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelMoreci.